By Michel Dejean, Head of CLS Fisheries Division. This article was first published in the INFOFISH International, Issue 3/2020 (May/June 2020).

Small-scale fisheries are a key part of the global Blue Economy, accounting for an estimated 50% of the global catch. There are increasing calls to monitor their activity, as today they are not regulated and do not benefit from the technology that has proved successful for industrial fishing. But simply applying the same methods used for industrial fishing will not work. We need a completely different approach, one that empowers these fishers, involves them from the beginning, and gives them the right tools to fish better and more safely.

Introduction

Around the world, it is increasingly recognised that ocean resources are finite, and fisheries need to adopt sustainable practices if they are to have any long-term future at all. Regulation of large industrial fisheries started some 30 years ago; for the vast majority of the fleet, their practices, locations and catches are all monitored and recorded. This has helped the authorities to tackle illegal fishing, allowing them to halt or restrict activities in areas where fish stocks are threatened.

However, it is estimated that small-scale fisheries (SSF) account for 50 % of the global catch and 95 % of the world’s fishers. As a result, there is a growing push to include small scale fishing in fisheries management—to understand how much is caught, which species and where, and to put in place systems that empower these traditional communities. Added to which, the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) has stated its intention to work with regulatory authorities to end illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing by 2020. Small-scale fisheries account for most of the unregulated catch, but for many reasons, the approaches currently used to regulate largescale industrial fisheries are simply not going to work for SSF. We must take into account the unique specificities of traditional fishing.

Some Inherent Challenges

The monitoring and regulation of industrial fishing has been possible because the sector is partly funded through fines levied on rule-breakers and through permits and licenses sold. The big players are easily identified, and enforcement can be targeted accordingly. By comparison, few traditional fishers can afford the same type of equipment that industrial fisheries are required to install. Identifying all the small-scale fishers and then trying to impose fisheries management practices upon them in the same way is going to be virtually impossible as available resources simply do not exist to apply this kind of enforcement model to 50 million people.

Systems for managing SSF cannot therefore rely on an economic model based on licenses and fines as well as having fishers use the same tracking devices, unless that equipment cost is significantly reduced. This sounds simple, but as you begin to include smaller categories of vessels, the number of boats to monitor increases exponentially. Resourcing this level of management becomes ever more challenging.

In practice, monitoring small-scale fisheries means a flag state will need to scale from managing a few thousand vessels to upwards of tens or hundreds of thousands, with their vessel IDs, licenses, time and zones of fishing, catch reports, and so on. This will generate an incredible volume of data, far exceeding the capacities of existing systems. Adapting for SSF means not just adding more vessels; we must redesign management platforms to pre-digest all that data and present it in ways that are actionable for stakeholders and decision-makers.

In addition, small-scale fishers’ everyday work differs considerably. For example, they may fish any species they find while using a variety of traditional fishing gears. They often fish in groups; many are not full-time fishermen (they may also be farmers or raise livestock outside of the fishing season). They do not necessarily have an expensive boat, gear or investments to amortise, so they think of their fishing activity differently. If we simply copy the industrial model, regulating things like mesh size of the net, or quotas based on a limited list of species, it clearly will not work.

Small fishing communities are also very different: in most cases, their fishing traditions have not changed for generations and are an integral part of the community’s identity. Moreover, the level of education can prove to be a challenge. For these reasons, if an external agency comes into the village to apply a new regulation from the top down, it will not work.

A Whole New Approach is Needed

There are clear benefits to better SSF monitoring, but the approach must be collaborative. Traditional fishers need to be involved in developing these systems, getting their feedback from the beginning. Not only does this ensure it meets their needs, but they can also see the benefits. This encourages them to adopt new practices and fosters greater stakeholder engagement. In other words, we will need to demonstrate these benefits to secure local fishers’ involvement, but in doing so, those clear benefits will then support collaboration moving forward. In formulating a possible new approach, there are several factors that need to be considered.

A Different Economic Model

First, equipment and services for traditional fishers must be inexpensive and easy to use in order to be a viable solution. But in addition, we need to think of new ways to finance SSF monitoring. Recent technology advances have enabled new transmitters that are more affordable and better suited to SSF needs, but who will pay for them? In some cases, an NGO or international development agency may step in and pay for the devices. This is good news for the fishermen, but raises questions about the long-term: will the system work when the project is finished and the agencies (and their funding) leave?

In some areas, we have seen the fishermen’s association play a large role, paying for the monitoring technology for their members, or in other cases, governments are choosing to set up public-private partnerships.

Data Collection

The first issue we need to address is the considerable data gap in these fisheries, to gain better knowledge about where, when, and how much they fish. Accurate information is the first step to taking decisions to protect fishers, food security, and fish stocks. The FAO’s Guidelines for Securing SSF calls for “the establishment of monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) systems applicable to and suitable for small-scale fisheries” and “systems of collecting fisheries data with a view to ensuring sustainability of ecosystems, including fish stocks, in a transparent manner.”

To achieve this goal, we need tracking devices adapted for these vessels, meaning that they be affordable, of course, and at the same time they also collect data automatically, requiring no action on the fisherman’s side: just install and then fish. The devices for tracking SSF must also provide a secure data chain, be tamper-proof and theft-proof, and able to collect data wherever they fish. For this, a simple GPS or smartphone is not enough, because these fishers are often forced to go far from shore, outside of mobile phone range.

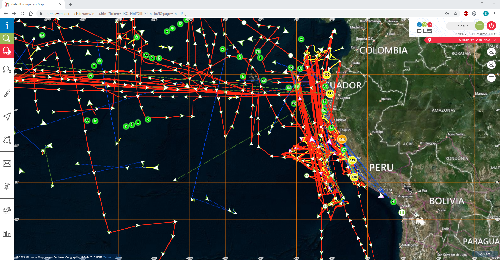

In addition, we need more than just location data; we need to know when and where they are fishing if we want to manage marine resources. Some have suggested AIS devices for fishermen. While they would help avoid collisions, once outside of coastal coverage, the delivery of AIS position reports by satellite often has saturation problems, meaning the data they provide would not be complete. A vessel monitoring terminal (VMS) is the only system recognised by the FAO for sustainable fisheries management, because the data chain is entirely secure and it collects data on fishing activity, not just locations.

Data Management

In addition to choosing the right equipment, we have to think about how to manage all the data generated. Software for fisheries monitoring centres (FMCs) will have to scale up to handling tens of thousands of vessels. Relying on paper logbooks or even spreadsheets is out of the question—we need user-friendly electronic catch reporting apps in order to handle these numbers of fishers. From the IT infrastructure point of view, the last decade has seen great progress in Big Data analytics. This enables us to face the challenge posed by the huge amount of information generated by SSF that must be processed, stored and the relevant indicators extracted.

The fisheries monitoring centres should also be perceived differently, not simply as centres to track vessel movements. In fact, the data they receive can help identify trends, indicators, and a whole level of information whose benefits can then cycle back to fishers, such as identifying the best areas to fish and new market opportunities. By working together, FMCs and SSFs can ensure that their region and community does indeed have a sustainable future.

Benefits for Small-scale Fishers

Connecting Fishers: Enhanced Safety

The support of a SSF community would be secured by helping make fishing activities operationally safer. Most traditional fishing communities have experienced loss of life at sea when the vessel’s motor dies and they cannot call for help, or a violent storm comes, or they are attacked by pirates. So, technology that enhances their safety is well received, especially as many now fish further and further from the coast.

For example, at Collecte Localisation Satellites (CLS), a device has been developed for these fishers to enhance their safety at sea. It has an assistance button and when activated, a message is sent to the fisher’s family or friends, fellow fishermen, or the authorities, depending on the configuration. The device also provides weather forecasts and sends typhoon alerts, so fishermen can head home in time.

There is another app where families can ‘follow’ fishermen on their trips, giving them a sense of reassurance. This benefits not only fishers and their families but also the viability of their communities and the local economy.

Protecting Fishers: Exclusive Fishing Zones

Another key issue facing SSF communities is conflict with industrial fishing vessels, in terms of competition for fish resources as well as collisions. A solution to this issue is the creation of zones reserved for small fishers. This approach follows the FAO’s SSF Guidelines that, “Small-scale fishing communities need to have secure tenure rights to the resources that form the basis for their…sustainable development” and “The creation and enforcement of exclusive zones for smallscale fisheries should be considered.”

But in order to establish a protected SSF zone, we first need data about where they fish, as mentioned above. Tracking them will provide the actual location where small-scale fishers are operating, enabling us to better define and enforce zones where industrial fishing vessels would be forbidden, and thereby preserving resources as well as avoiding collisions.

For example, in Peru, the government has reserved the first five nautical miles from the coast for traditional fishers. However the fishermen CLS representatives spoke with, want that zone extended to 40 nautical miles because that is where higher-value species such as tuna are found. For the moment, they have no tracking data to prove to the government that they fish in those zones, but once they have a vessel monitoring system, they will have such data to support their claims.

Empowering Fishers: Traceability and Improving Market Access

Increasingly, market considerations are a compelling reason for small-scale fishers to adopt monitoring systems. Gaining access to export markets would improve their incomes and help develop their local economies – for instance, there is growing international demand for one-by-one caught tuna.

Consumers in Europe and the West, two of the highest value export markets, are demanding to know more about the supply chain, traceability and sustainability of the food they consume. Exporting to the EU requires proof that the fish was caught legally, which is not yet possible for small-scale fishers. To be part of this wider supply chain, they need a vessel monitoring system (VMS) and a set of catch reporting and traceability applications.

In our work, we have seen that small fishers are starting to get involved with marketing and international markets. For example, large distribution groups such as Walmart are

increasingly contracting directly with local fishers’ associations to supply their stores. Here, it is important to differentiate small-scale fishers from poverty-stricken fishers. In Bali, for example, and many other places, very small boats (pole and line) are catching 1-2 fish per trip, but these fish are sold for good prices and are exported directly to the US or Japan.

In another case, a fishermen’s association we worked with in Peru wants to set up a Quality Label for its members. Their line fishing method has no bycatch, so is more environmentally friendly, and the fish are of exceptional quality. With this traceability label, they can sell directly to upscale restaurants in Lima, and with the improved income they can develop their communities. By providing them with tracking and traceability technology, we can empower them with the tools they need for community development.

Empowering Fishers: Adapting to Climate Change

Another issue of concern for small-scale fishing communities is the impact of climate change, as in some areas, fish stocks seem to be shifting. This is definitely an issue for continued research and management efforts.

More data is needed on coastal fisheries, their catches, and species, but we already know how to make predictions about where certain fish stocks will shift in relation to changing ocean conditions. At CLS, there is a Marine Ecosystem Modeling team of experts who study precisely this question. (See “Pacific Tuna & Climate: Trends & Forecasts” published in the INFOFISH International). They have assessed the impacts on, for example, tuna stocks in the Pacific, and can predict where they will shift over the next 20 years. They can also test different scenarios depending on fishing efforts and various climate change indicators, to help determine sustainable fishing levels or where to locate processing plants.

These kinds of studies need to be further developed for the zones and species specific to small-scale fishers. The results can then be used to send them information on favourable fishing grounds, helping them to spend less time looking for their catch and enabling them to avoid areas of juvenile fish, for example, which would help protect stocks and resources for the future.

Collaboration is Key

In sum, we will need to prove the benefits of monitoring to secure local fishers’ engagement, but those clear benefits will then support collaboration moving forward.

The European project STARFISH 4.0 led by CLS is an example of this approach working in practice. The project trials new VMS technology for small-scale fishers that will be developed with the local fishers’ feedback. In this way, small-scale fishers are involved and empowered in designing the systems that best suit their needs. Europe chose the STARFISH 4.0 project precisely because it adopts a participatory approach, building a culture of compliance among traditional fishers before the regulation comes into force. CLS, local partners, fishermen’s associations, and local communities are all working together to develop a device and mobile apps that have value for fishermen. In effect it secures engagement, building positive productive relationships long before any regulation comes into effect.

All around the world, governments, regulators and NGOs are trying to work out how to manage SSFs effectively. SSFs are small, extremely diverse and numerous, so the approach taken with industrial large-scale fisheries simply will not work. A new participatory, collaborative mindset is needed, along with the necessary new technology, and with SSF and regulators working together to build a safe and sustainable fishing future for everyone.

Michel Dejean (mdejean@groupcls.com) joined Collecte Localisation Satellites (CLS) in 1997. Over his career, he has worked in almost every aspect of fisheries monitoring with governments, NGOs and fishermen around the world. From 2012 to 2018 he was head of the CLS Indonesia office and was named Director of CLS Group’s Fisheries Division in 2018, a position he holds till today. Over the last 22 years, the main change he has seen has been in the attitude of fishers and regulators, from confrontational opposition in the past to increasing convergence as they acknowledge that sustainability has to be the end goal for all—a change he welcomes.